Chasing a Feeling

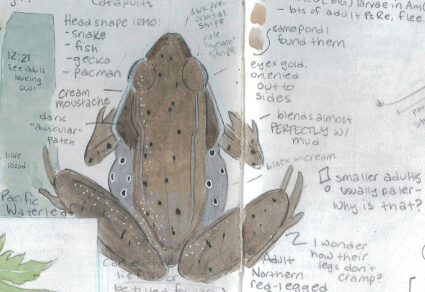

I scramble toward solid ground, tripping over fallen branches onto the elk path leading deeper into the woods. Cottonwood fragrance fills the air and songs of robins, Pacific wrens, and woodpeckers produce a delightful spring cacophony. I take another step and a dull ‘plop’ alerts me to a large adult red-legged frog fleeing my boot. They don’t make another move and I recognize my opportunity. For a moment I hesitate. Frogs are a challenging subject for me and I worry about ‘messing up’ or ‘doing it wrong’. Reminding myself that it’s the depth of observation I bring to this little creature and not the outcome on paper that matters to me I take a deep breath, perch on a dry branch out of the mud, and begin blocking in the shape on my page with my pencil. My first hesitant sketch doesn’t look quite like my subject, but I can feel myself tuning in and calming down. That awkward sacrificial pancake paves the way path to the next sketch. I start another sketch of the frog, this time paying closer attention to my subject who sits patiently on the ground next to me. I can tell they’re aware of me but for the moment we have a tentative truce. “I won’t bother you,” I promise. “I just want to do your portrait.” The frog shifts slightly at the sound of my voice but doesn’t leap away.

Within a few minutes I’m through with my careful contour sketch and feel satisfied with it. I could stop now and move on, but wouldn’t it be even better to record color notes of this frog? A new fear seizes me: should I add watercolor? I’ve gotten to where I usually feel reasonably confident with my pencil drawings, but my watercolor skill hasn’t kept pace, mostly because I allow my fear to get the better of me. I worry that I’ll ruin an otherwise ‘acceptable’ drawing and easily become paralyzed by apprehension. I take a moment to acknowledge that feeling but making a conscious decision not to let it to overwhelm me, reminding myself that the key to improving my watercolor is to get more Brush Miles in and that the goal of my journaling is not to produce pretty pictures but to notice more, observe more deeply, and experience more richly.

I pull my watercolor palette from my field bag and pull my paint sock onto my wrist. I begin to paint, beginning with shadows and gradually building up colors and values. Slowly, I feel something in my experience shift. As I pull my brush across the paper, my eyes flitting from the frog to my sketch and back again, the details of my environment begin to crystallize. I feel the gentle buzz of enjoyment and wellbeing wash over me and a thought spontaneously occurs to me that, “This is the good stuff!” In this moment the image on paper is only a bonus. I’m observing in a way that eclipses simply “looking” at a frog. This convergence of attention, curiosity, and total absorption in the moment—this is why I nature journal!

The Scenic Route

Growing up I’d always been interested in art and nature but it took me a long time to figure out how to combine them. As a kid I wanted to be an animator for feature films but ignored the advice of professionals to draw from life. Mostly I liked to trace and copy cartoons for fun and I liked it when grown-ups told me my art was Good. I quickly learned that people generally only saw drawing as worthwhile if the results could be judged as Good, and being Good At Art became very important to me. The problem was that the road to Good is a long trek through learning and hours of practice and almost requires a dedication to making art for its own sake. This obsession with perfection and making Good Art (whatever that means) would hound me for years, but I eventually I did learn to balance the creative impulse that drives me to keep sketchbooks with the inner gremlin that tries to convince me my work isn’t good enough. It seems like life was going to keep presenting me with opportunities to learn this lesson no matter how long it took or how I stubborn I chose to be!

At age nine I announced to my daycare teacher that I wanted to take nature notes like my idols in National Geographic did. She handed me a pencil and paper and led me to the edge of the daycare playground where I faced an impenetrable wall of English ivy. A couple furtive, skittish birds skulked in the shadows. This was nothing like the clear views of wildlife I enjoyed in nature documentaries! I was automatically overwhelmed and lost my nerve, not sure where to even begin. In elementary school we were given little notebooks and encouraged to go out and explore with them. I checked out a book about pill bugs from the school library and examined living specimens under logs but was totally petrified when it came to recording notes about them. What was my page supposed to look like? How did I know if I was doing it right? I hid that notebook under the couch and tried to forget about it.

I wouldn’t revisit nature journaling till I was fourteen. I was deep into a preoccupation with sub-Saharan Africa and had my mind made up to be a game ranger in South Africa’s Kruger National Park. I even had a map of South Africa posted above my bed! There was just one problem. I didn’t know the first thing about South Africa’s native plants or birds, I’d never seen a reedbuck, and couldn’t tell spoor from pugmarks. Then it occurred to me: why didn’t I practice on the local environment? Surely if I became knowledgeable about Pacific northwest natural history it would be a transferable skill and I could pick up bushveld natural history no problem. At some point while concocting this genius plan I came across an image of biologist George Schaller’s field notes from his studies of Serengeti lions in the 1960s. The notes were meticulous, handwritten in small tidy script on quad-ruled paper. For some reason this photograph gripped my imagination and lit a fire in my belly.

Something about it made sense to me and the very next day I marched to the store and bought a graph notebook and began keeping a nature journal. I kept notes made in the field in an old reporter’s notebook, eventually upgrading to a series of waterproof journals that could withstand Pacific northwest downpours and dunks in wetland mud. The freedom of the field books, which I felt safe letting be scribbly affairs, allowed me to record unselfconsciously. At my desk back at home I would stitch a story together in my journal from my field notebook. This worked well for me through my teen years. I fell so deeply in love with the cottonwood river bottoms and northwest bird songs of my neighborhood that I eventually discarded my game ranger ambitions and began focusing entirely on my local bioregion.

But my nature journal system could be frustrating and fussy. It was time-consuming and impractical to essentially journal twice for each experience. Sometimes it felt as though something was lost in translation between the event and the recording. And I missed out on the breathless exuberance of my field notes in my “finished” journal entries. Perhaps most painfully I eventually acknowledged that I was using the writing-only format to avoid drawing, which still scared me. I was captivated by Clare Walker Leslie’s book Keeping a Nature Journal and the loose, fearless approach she took in her own sketchbooks. Maybe that was something I could do? I occasionally sketched in my journals, but was afraid to go as big and bold as Leslie seemed to do so effortlessly. I stuck with my imperfect system longer than I should have, muscling through the friction I felt but not ready to make the leap to unlined paper and a focus on drawing.

In my early twenties I dispensed with the quad notebooks altogether, that collection of journals discarded one morning in a spasm of dread, casualties of my neurotic habit of throwing things away when I feel overcome by anxiety or indecision. Maybe I just wanted to wipe the slate clean. Still, many of the discoveries I had catalogued in those early journals remain clear and vivid to me, a testament to the power of journaling to support memory. For a number of years, busy with a demanding AmeriCorps I stuck to my scribbly field notebooks, stream-of-consciousness recordings of my experiences and observations exploring Seattle greenspaces and beaches at all hours on my bike. These were very intense, almost transcendental experiences – some nights, long after dark on some cobbly beach, I would look up and realize I was accompanied by racoons, or find myself at sunrise on a bluff overlooking Elliot Bay morning fog obscuring the city skyline so that I felt as if I had slipped through a wormhole to a precolonial time.

After a few years of haphazard nature-notebooking I eventually gave that up too. I still kept personal sketchbooks. I sketched people covertly on my long bus commutes, attended figure drawing classes, dabbled in urban sketching, and liked to draw cartoons about my life, but I avoided nature journaling out of feelings of inadequacy. Around this time, I discovered a copy of the Laws Guide to Nature Drawing and Journaling and was enthralled by it. The first time I leafed through those pages I found tears welling up in my eyes. Jack seemed to feel the same way about nature that I did, and he was actually doing something about it! He wrote with such tenderness and reverence, and while I felt intimidated by the skill evident in his drawings, his friendly approach was encouraging. I kept a procession of unfinished nature journals in the following years, always abandoning them before they were completed. Eventually mental and physical health challenges derailed these efforts and I paused nature journaling. But I always felt a quiet desire to return to the practice, and even privately promised myself that one day, when I felt ready, I would pick up a journal and try again.

The Breakthrough

Like many of us who rekindled abandoned or neglected hobbies during the yawning chunks of time presented by the COVID-19 lockdowns, I revisited nature journaling, this time in earnest, at the beginning of 2020. I had been hemming and hawing about giving it another go, my inner gremlin dragging me down with such unhelpful contributions as “if you couldn’t stick with it before, what makes you think you will this it this time around?” But something changed when I stumbled across Marley Peiffer’s Unlock Your Potential video. I started watching it on a morning I’d already well overslept, newly laid-off, feeling stuck and inert. Just a few minutes in and I was riveted. I started scrawling notes in my pajamas. Learning about the concept of growth mindset initiated a cognitive shift, and it’s the reason I started nature journaling again and have stuck with it for the last two years (take that, gremlin!).

I realized that this practice could be a haven from my perceived need for perfection. I didn’t have to share my journal pages with anyone if I didn’t want to. I could make sloppy, messy pages, and it was just fine. I could work painstakingly on a journal entry if I wanted, or dash four pages’ worth of notes in a few short minutes if I chose. Everything I did in my journal was great, and if I didn’t like something I wrote or drew I could simply turn the page and start a new one. I tossed that unhelpful standard of making Good Drawings I’d been schlepping around since childhood and instead focused on making lots of drawings, and then lots more drawings. If I felt discouraged about a drawing I took some of John Muir Laws’ advice and turned it into a diagram. I decided to measure the success of my drawings not by aesthetic prettiness but by whether I recorded something interesting, noticed something new, or enriched my experience in nature. Most importantly, I was having the time of my life! I couldn’t get enough.

I realized with delight one day while sketching complicated leaf shapes that awkward ‘first-attempt’ drawings are tangible records of your brain grappling with something new and challenging. The next drawing is a little better. This one after that, a bit better than before. The very next might be a total flop, as I tried a different approach or forced myself to draw less deliberately and more boldly. But eventually, with repeated practice and persistence, I would get closer to describing what I saw with greater accuracy, with the bonus that by the end of the process I knew my subject much better than I ever would have had I simply plucked a leaf and inspected it without taking written or visual notes.

I was intimidated by drawing birds, who seemed to know just when I started to sketch them and would fly away the minute I looked down at my paper. But I practiced deliberately, studying references at home and watching John Muir Laws videos when the weather was terrible. Just when I started to feel confident about my quick-draw bird sketching capabilities, a pair of black-tailed deer wandered into my backyard and as I scrawled sketches in my journal I realized that I did not have a very good foundational knowledge of drawing ungulates. I started studying deer and elk skeletons, muscles, poses, and even the details of dead elk my dog Niko and I found in the woods near our home. I copied Bill Berry’s caribou drawings to get inside his head and really learn how to construct the forms of these animals. Now I feel a lot more confident quickly sketching elk I see around my home, worrying not so much about the drawing part but focusing on recording my observations faithfully.

In the first couple years of this process I would often find myself exhausted and discouraged at some point by a perceived lack of progress. I would need to take an extended break of a couple weeks up to even a few months from my journaling. I would feel ashamed of my perceived failure but after experiencing a few cycles of this phenomenon I realized that creativity seems to work like a muscle. If you want a stronger muscle you have to push that muscle to perform beyond its current ability, but you can’t keep working out the muscle without a break or you’ll injure yourself. You have to let that sore muscle heal from the stress of the exercise by giving it lots of rest, fuel, stretches and active recovery. With nature journaling or any other kind of creative skill building, the principles are the same.

I might spend a lot of time for a couple weeks intensively practicing drawing elk or insects, but eventually I’ll exhaust my brain’s capacity for practice. Now when I feel tapped-out I take a break. I draw something else, write in my journal, or do lower-effort journal entries. If my hand and brain simply refuse to cooperate I find other ways to engage my brain. I go on walks with my dog, take naps, read, watch movies or play video games, or study other artists’ work for inspiration. Without fail, after a few days that little creative imp starts to nudge me back to my journal, and I find that when I return to my challenging subject, I have a better handle on it than I did before.

This approach to nature journaling totally changed my relationship with art and creativity. Rather than being an agonizing experience of feeling like a failure and giving up, it’s a joyful, sometimes frustrating, but ultimately always rewarding experience. Rather than fall into the “pretty picture” trap and beat myself up about my performance, I focus on the pleasure of being outdoors and the gratitude I feel for the opportunity to observe and experience and discover for myself with my journal as my mentor.

Your Turn!

My journey to nature journaling has been a bumpy and nonlinear one. Susceptible to self-doubt and prone to frustration, there were many times I wanted to throw in the towel, but a tiny ember of that creative impulse never let me really give it up, no matter how discouraged I felt. I hope that if you’re struggling with your nature journal practice, whether it’s been a long time since you’ve even cracked the spine on your journal and you’re feeling guilty or negative about the experience, feel stuck in a rut, or if you’ve always wanted to try but you’re terrified of messing up or doing it wrong, you’re willing to give it just one more shot. And then another one after that. Each new page is a new opportunity and I hope you take every one.

About the Author

Sawnch was born in Seattle and grew up all over the Puget-Willamette Lowlands Bioregion. These days I live in Packwood, Washington and love exploring my environment with binoculars and trusty nature journal kit by my side. If you would like to get in touch with Sawnch, you can email: okinokee@gmail.com.