Mushrooms are my absolute favorite subjects for nature journaling, so I am excited to share some tips and techniques for observing and appreciating fungi with the use of a journal!

Fungi are very diverse, surprising, mysterious, and often fleeting features of the natural landscape. Their non-determinate growth, rapid fruiting cycle, seasonality, and fussy habitat preferences would pique the curiosity of any naturalist. There is so much to learn about fungi, though I believe that they will always hold mysteries no matter how much we study them.

Nature journalists love subjects that allow for deep inquiry. We like to ask questions not to find answers, but to find deeper questions. We relish in curiosity and wonder, mystery and confusion. A single collection of mushrooms can offer many hours, even days of fodder for a nature journalist.

Gathering

Mushrooms (along with shelves, jellies, puffballs, and cups) are the fruiting bodies of the organism, which is otherwise integrated into the substrate as a system of cells called mycelium. Like plucking an apple from the tree, picking the mushroom does not kill the fungus, so it is perfectly acceptable to gather mushrooms for closer examination.

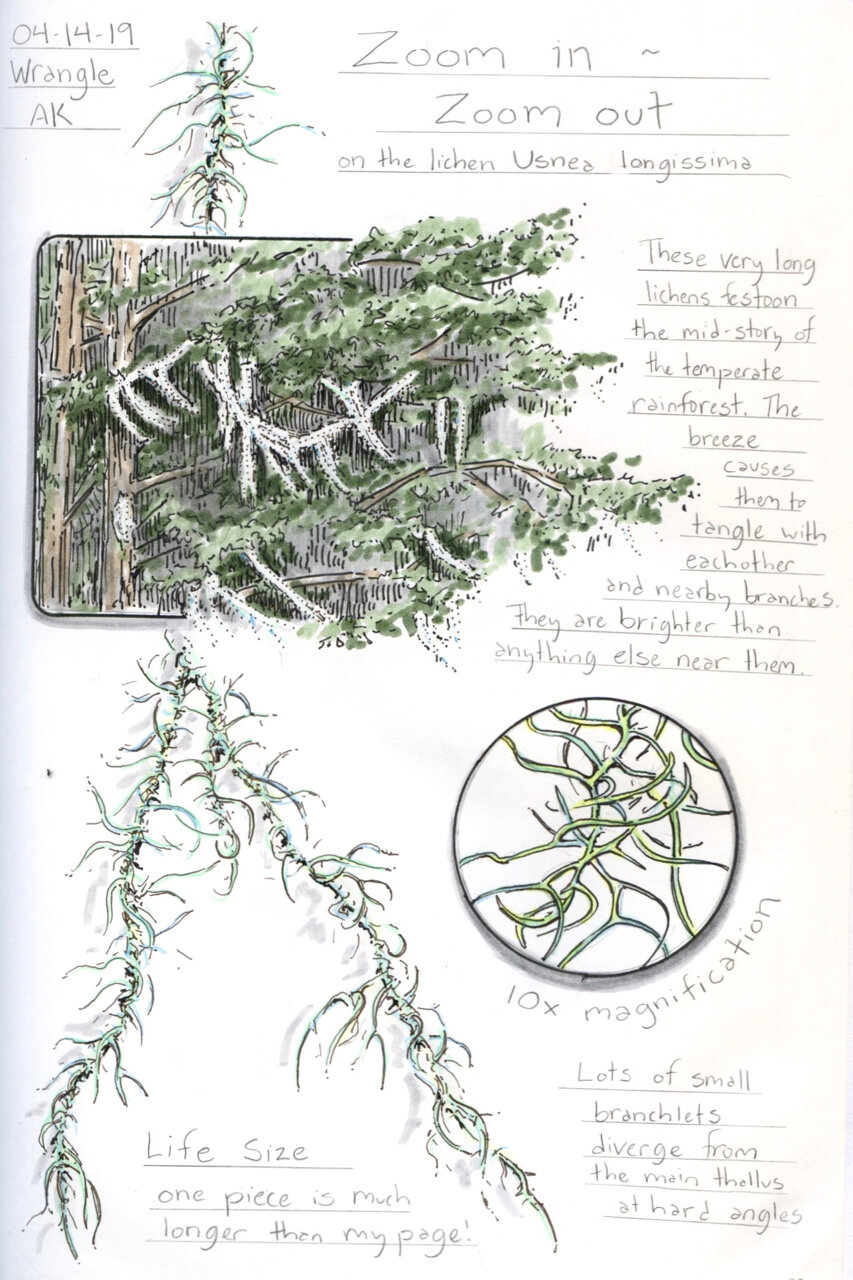

Lichens (or lichenized fungi) are a whole package of fungal fruiting bodies, mycelium and symbiotic algae and/or cyanobacteria. They are slow growing and should be collected sparingly, ideally from fallen branches.

When gathering mushrooms, take note of your surrounding habitat, especially the tree species. Many mushrooms grow in association with tree roots, and are only found under certain kinds of trees.

Take detailed notes of the substrate type. Are they growing from the ground, a log, wood chips, or a grassy lawn? What kind of ground, what type of wood? It is especially important to note hard wood vs. soft wood, living wood vs. dead wood, and other features may be important too, such as how decomposed it is. There are some fungi that grow specifically on strange substrates such as dung, cones, and even carpet!

When you find mushrooms, notice the growth arrangements. Is it solitary, or in a cluster, are they scattered gregariously, or growing in fairy ring? Consider making a sketch of their growth habits, or a ‘landscapito’ of their preferred habitat type.

When picking a mushroom, be sure to collect the whole thing. Avoid cutting the stipe (stalk) if you can, instead dig it out. There may be some interesting features in the stipe that are important, and you may even find that it is growing from something that is buried under the surface. If you can, collect a range of ages, from young buttons to ones that have fully matured.

Immediately after you pick, take a close look at the coloration. Are there any faint tints of hues that might fade over time? Is there cottony powder, or cobwebby material? Is it bruising and if so what is the color of the bruise when it is fresh? Does the fungus have a unique odor or fragrance?

Has the fungus released spores onto nearby surfaces, and if so what are their color? For shelf fungi, sometimes the spores form a film on the top of the shelf. If the conditions are right, you can sometimes see spores release from cup fungi by breathing into the cup, like you would do to fog a pair of glasses before cleaning them.

Treat your specimens gently, or they will soon lose much of their beauty and appeal. Clean off debris with a brush before stowing them. I like to put mine in a small pail, but Tupperware, baskets, or paper bags work as well. Avoid plastic bags if possible, they will suffocate and squish the mushrooms. Keep specimens cool, or in the fridge until you are ready to look at them, but ideally you would get started right away.

Lichens are extremely hardy, desiccate perfectly, and can remain viable for long periods of time. Rehydrate them with a spray bottle before getting started and they will spring back to life!

FIELD NOTES:

Habitat Type

Tree Species

Substrate

Growth/Distribution Patterns

Fragrance/Odor

Bruising

Faint Colorations

Delicate Features

Examining the details

When mushroom season hits, I like to set up a workstation for my investigations. Cover a table in newspaper and hope that your family is participating, encouraging, or at least tolerant of your hobby.

In addition to my journaling supplies, I also like to have field guides, a cutting surface, containers and trays, dissection kit or a knife, white and black paper for spore prints, ruler, hand lens/magnifier, and a compound microscope.

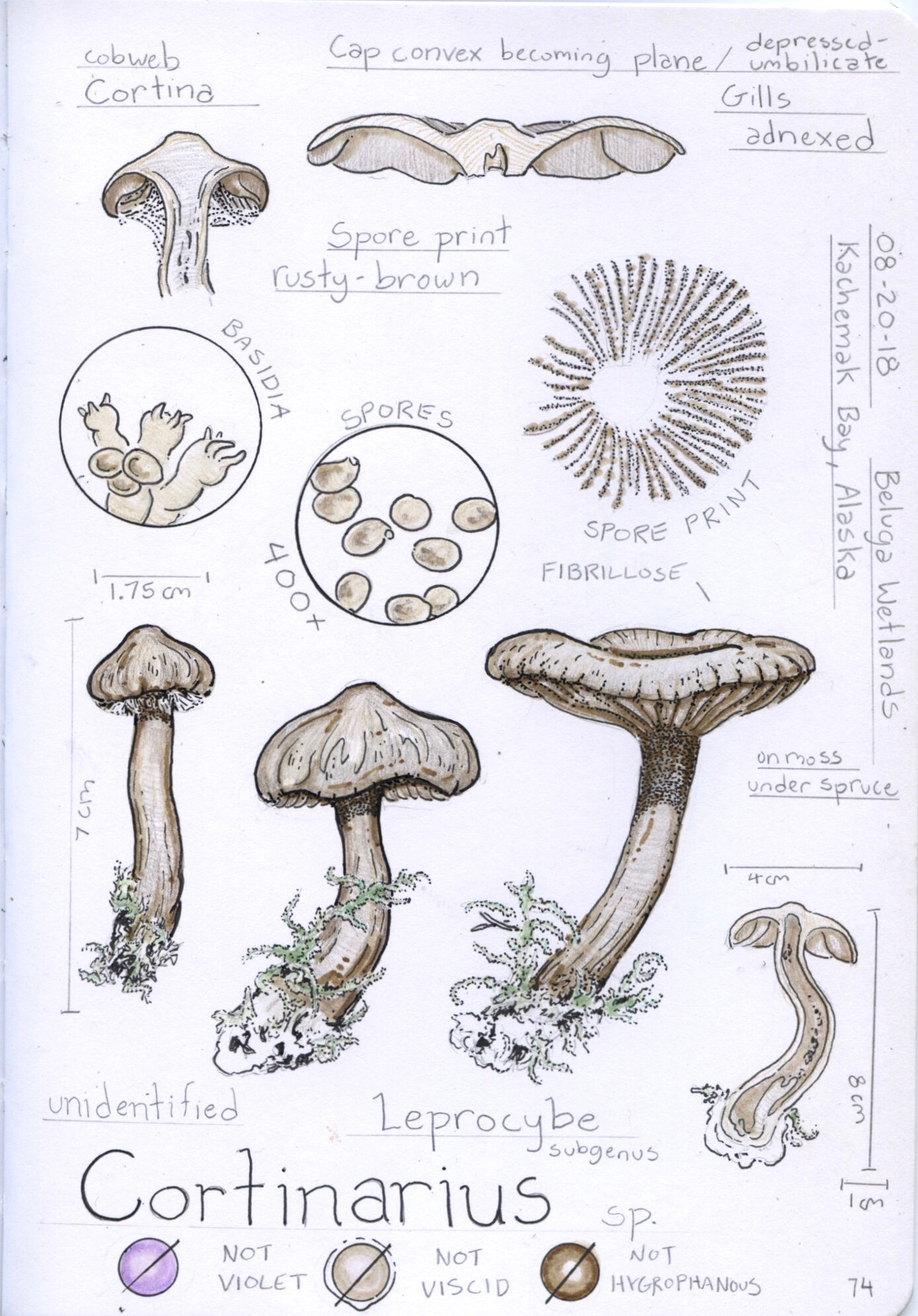

I usually start by sketching the mushroom or if there are multiple, sketch the different growth phases. As nature journalists know, drawing focuses attention and causes us to notice more details. I usually end up taking my mushrooms apart, so I like to be sure to have my drawings at least outlined before I begin dissecting them. I like to orient my mushrooms so that I can see both the underside and the top of the cap in one view.

Even if you wont be coloring your page, take notes on the coloration of all parts, including gills, cap, and stipe. Colors may fade with age, so noting the color can be important for identification later on. Look for coloration and texture patterns, such as concentric rings on the cap or features on the cap margin.

Once I have my mushrooms sketched, I like to prepare a spore print. If you are interested in identifying your specimen, then learning the spore color is usually the first and most crucial step.

To take a spore print, remove a mature cap, and place it on sturdy paper with the gills facing down. Place an overturned bowl on top, and if the cap is dry, put a bead of water on top. Avoid soggy caps, as they will just leave a water stain. Ideally, leave it to print overnight. Some caps drop billions of spores quickly, while others may never really give you a good print. Many mushrooms have white spores, so some people use half white/half black paper, but I find that white spores are easily visible even on white paper. I have had some success in preserving spore prints by carefully covering them with a strip of packaging tape, but drawing the spore print might make a longer lasting image.

Most mushroom field guides have diagrams of various features and terminology for fungi. This is a great way to start to examine your mushrooms. See how many features you can identify about your specimens.

If your mushroom has gills (as opposed to pores, teeth, cups, or some other spore bearing surface), then you will want to take a close look at them. Are they attached to the stipe/stalk, or can you easily remove the cap from the stipe without tearing the gills? Do the gills run down the stalk? Are they distant or crowded? Check young specimens for gill color. Once the mushroom releases spores, the gills might change color due to the spores.

Notice additional features such as veil remnants (when the cap separates from the stipe, it may leave a skirt or other such clues), overall shape of the cap and stipe, measurements, and the texture of the flesh. To take a cross section, you can often just pull the mushroom apart in a perfect division.

If you have a compound microscope, you can take a look at the spores. Spore shape can sometimes be necessary for identification, but I like to check them out and include them in my journal page regardless. If you don't have a microscope, a hand lens or magnifying glass will allow you to see tiny features such as scales or fishnet patterns on the surface of your mushrooms.

EXAMINE:

Type of spore-bearing surface (gills, pores, cups, teeth, etc.)

Gill attachment, color and spacing (if present)

Cap shape

Stipe shape, texture, and fill (if present)

Spore print color and spore shape

Texturing, ornamentation, other unique features

The identification challenge

I actually started keeping a nature journal as part of a mycology course, because identifying mushrooms requires detailed habitat notes, dissections, microscopic examination, and deductive reasoning through the use of dichotomous keys. A nature journal is the perfect thing to keep track of this landslide of information.

Mushroom identification is both challenging and attainable. It requires practice and learned familiarity – things that nature journaling has prepared you for! Embrace the unknown. Do not be disappointed when you cannot identify the fungi that you find. It will happen.

Also, do not expect your identified mushrooms to have common names. While common names for birds are highly reliable, common names for fungi are highly non-existent! Sometimes I feel like publishers simply make them up for the sake of standardized formatting. I suppose that the people who care enough to discern many of the types of fungi are the same that also enjoy learning the scientific names, and this particular field is where the reliability is very significant.

Chances are high that the mushroom you found isn’t even in the field guide that you have, but there is still a huge value in trying to identify them anyway, as long as you aren’t attached to finding an answer. The process will cause you to scrutinize your mushroom and teach you what features you should be looking for. It will also help you hone in on the group of fungi that yours belongs to. Looking at field guides will familiarize you with common fungi, so when you see them in the field, you will recall them from the book, and you will be able to identify them.

When it comes to identification, I start with my tried and true copy of Mushrooms Demystified by David Aurora. This is a guide that uses dichotomous keys, which is the way to reliably identify fungi. It is a California based guide, but it covers United States and Canada. Even though I’m in Alaska, and many of the names have undergone revisions, I use it as my primary guide and have a large number of other smaller field guides that serve as cross-references, especially when it comes to photos.

If you want to get serious about identifying fungi, you must learn to use keys. One way to practice as a beginner is to find an obvious species that you know, and then use the key from the beginning until you reach the known outcome. Keys are challenging to learn, and with all challenges come some frustration, but once you get the hang of it, it’s like detective work as you rule out all the things that your mushroom is NOT until hopefully you land on what it IS. Mushrooms keys are especially bizarre, as your options might fluctuate between the microscopic features of a spore, to “sort of smells like red-hots and dirty socks”. The combination of objectively technical traits and whimsical impressions makes mushroom identification pretty entertaining.

If you feel like you’ve found it, double-check the descriptions and cross-reference with other guides. Online searches are sometimes helpful with confirmations, but be wary! Information and photos of the more obscure fungi are very scant and unreliable through general search methods.

I have a few great guides that are specific to my region and have many of our most common species. I suggest finding the most regionally specific guides that you can.

It is the vast diversity and short windows of opportunities that have kept me intrigued and engaged with fungi identification for over 10 years. Just do your best, and embrace the challenge!

Foraging for edibles

I absolutely love foraging for wild edible mushrooms. Similar to keeping a nature journal, wild foraging will cause you to see your natural environment with new eyes. Soon you will be picking up on habitat clues that you had never considered before, such as angle and aspect of slope, age and species of tree stands, understory composition and humidity, and a whole host of other factors that will lend to a holistic and intuitive understanding of the ecosystems that fungi inhabit.

Mushroom hunting nurtures a 6th sense. No other activity has me scrambling under logs and jumping over fences quite like mushroom hunting. I find myself in the most unlikely places simply because I have a hunch that I might find a delectable edible in the vicinity. They don’t necessarily grow where it’s easy to search for them!

I am an avid mushroom forager, but my appreciation and interest in mycology goes much deeper than that. “Can I eat this?” is by far the most common question I hear from people when it comes to mushrooms, and I find it a bit irksome. The answer theoretically could range from “yes it’s delicious” to “no, it will kill you” but probably falls under the spectrum of “if you like to eat cardboard” to “if you like to eat slimy mush”. Many mushrooms are technically edible, just like many plants are technically edible, but most of us don’t go around munching on the leaves and twigs in our yards.

Personal peeves aside, if mushroom edibility is the thing that inspires people to start learning about and appreciating mushrooms, then I highly encourage wild foraging! Despite popular warnings, you do not have to be an expert at identification to start wild foraging. The secret is to learn what wild edibles grow in your area, learn how to distinguish these from others or look-alikes, and simply target only those species.

Let the habitat guide you, as you learn what conditions favor your selected mushrooms. My friends and I call it “dec-hab”, short for decent habitat. This is the preferred approach to wild harvesting anyway, considering that there are so many species of fungi, and that they can be so difficult to identify with certainty. Better to seek the ones you know to be good, than to ask if the ones that you found are.

If you do find a nice basket of edibles, proceed with caution! Ask for a confirmation on your identification (pretty easy with all the online groups and forums these days). Eat only a small amount at first. Many people have allergic reactions or gastrointestinal intolerances to mushrooms, so ‘edibility’ can be different from person to person. Also, anyone can get sick from over-indulgence (I certainly have). I always thoroughly cook my mushrooms.

Wherever your fungal fancies may take you, I hope that these curious, weird and gorgeous growths will enhance your nature journaling and inquiry experience time and time again. Happy hunting!