“The two questions we should ask of any strong landscape are these: firstly, what do I know when I am in this place that I can know nowhere else? And then, vainly, what does this place know of me that I cannot know of myself?” ― Robert Macfarlane, The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot

I was always an outdoor person. A childhood spent with horses, on the commons near home. Years in the Young Farmers, long evenings playing rounders, tractor races and displays at the county show. After a failed foray into art school, I dropped out and trained as an environmental scientist. Then, after a little fieldwork, I retreated behind a desk and analysed the outside from inside.

Mid-twenties, I was diagnosed with “Seasonal Affective Disorder”. Not enough light, they said. Too affected by the seasons, they said. Winter blues and anti-depressants, anxious cycles and deepest lethargy. I would sit in front of a light box for several hours after work, clinging to the crisp blue rays, and wishing the winter away.

I remember one lunchtime in February, walking as I always did from my university department to the music practice rooms and passing a low hedge on campus. There, I saw amid the twigs that a few buds had swollen and greened. Each day thereafter, I watched that hedge as withered green peeped through the buds and unfurled, tiny hazel leaves like limp new butterflies with sodden wings, soon plumping and expanding. Shortly after, I found my way through yoga to Buddhism, and the world came alive to me.

Once the opportunity came to take my work freelance, I did so. My partner was made redundant at a similar time and we left the densely populated London commuter belt for the West Country. The first thing I did, in 2016, was begin my nature journals.

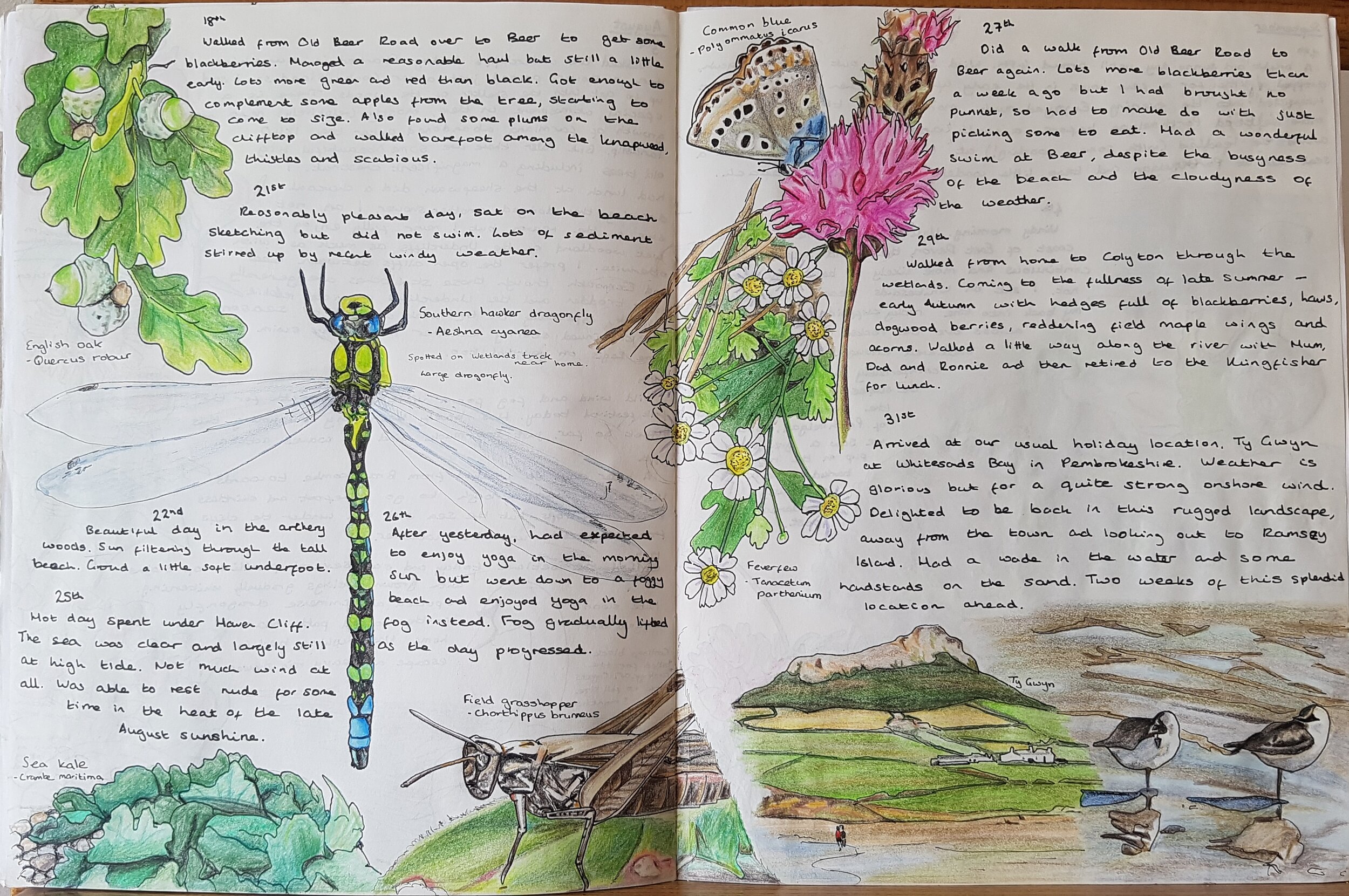

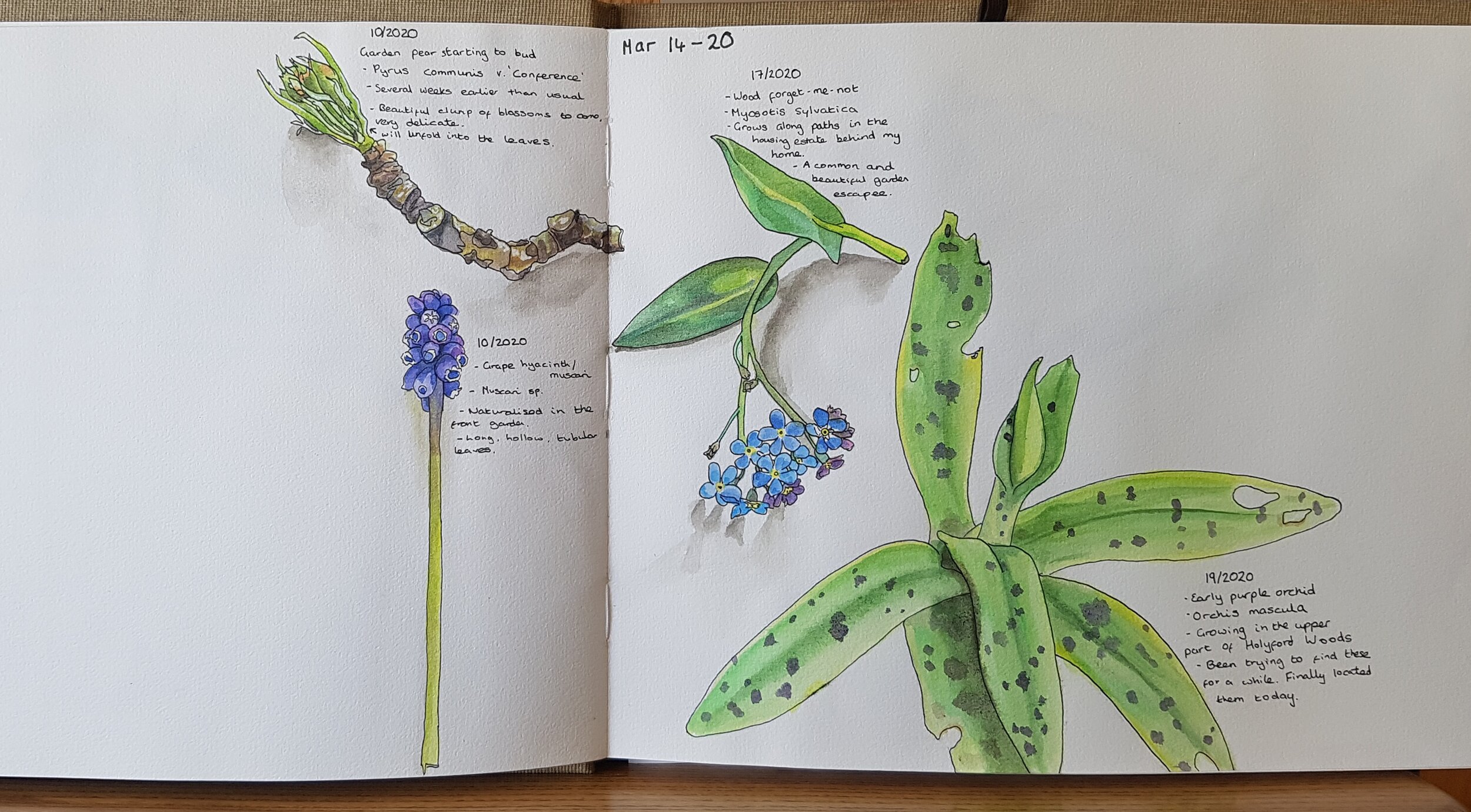

I keep three different nature journals now. One is like a diary. It keeps track of where I have been and what I saw there, usually drawing at home from photographs taken outdoors. The second is used to follow the plants and trees through the seasons, drawing from life either outdoors or from samples brought home. The last is my field book, a scrawling mess of words and pictures, that is free from ever needing to look “finished” and can be used expressively.

“Nature does not hurry yet everything is accomplished” ― Lao Tzu

These days, I spend a lot of time out of doors, either working on a drawing or piece of writing or just taking in a place. I think of all time outdoors as a meditation on the present, and practise keeping the past and future out of my thoughts. When I am in the field, when walking, or sat in meditation, I like to ask the question “What else is here?” Think on it a moment, what else is here? Other than thoughts, other than breath, other than sight, smell, sound. What moves in this moment? Continuous asking of this question when exploring a landscape or a place can help us to retain focus and experience more. You may even spot things you have never noticed before in a familiar place.

Try it yourself.

1) Pick a spot outside or by a window to stay in still presence for 5 to 10 minutes.

2) Ask yourself “What is here?” Maybe you notice the song of a great tit. And then “What else is here?” A primrose across the garden. And continue. Include sights, smells, sounds, sensations, thoughts. If you get lost in a thought, never mind. Once you notice, ask again “What else is here?” and continue. All of these things are a part of the experience.

3) After the time is up (you can use a timer, or just decide naturally when you are done), make a list, do a sketch of one of the things you noticed, or write a short account of your experience.

Finally, I would like to say that I no longer consider being affected by the seasons a “disorder” at all, but a rather a symptom of how disconnected modern life is from the natural world. After several years of a simpler freelance life, I am able to enjoy the winter, with no pills and no lightbox. My medicine is ensuring at least an hour a day outdoors, regardless of the weather. Most of that time is spent in observation of nature’s cycle and an enjoyment of the simple dormancy of winter, without yearning for spring. By staying connected to nature’s rhythms, we can shed our ritualised detachment from the natural world. Considering that this severance is a source of so many of the threats to nature, and to our own well-being, this can only be encouraged. David Attenborough said, after all, “No one will protect what they don’t care about, and no one will care about what they have never experienced.”